Like many other people, I have often had the experience of setting an alarm clock and then waking just before it went off. At first, when I used old-style, windup alarm clocks, I assumed that this was because I heard the click that such clocks often made shortly before they went off. But then I found that the same thing happened with electronic alarm clocks, with no preliminary mechanical sound.

Without thinking about it very much, I assumed that the phenomenon must depend on an intrinsic time sense or “biological clock.” Human beings, like many other organisms, have intrinsic daily rhythms, often called circadian rhythms, which underlie daily cycles such as waking and sleeping. The biological clock seemed likely to provide an explanation for this ability to wake at a particular time, although the details as to how this might happen were vague. For years I took this theory for granted, and found that most other people assumed there must be some explanation of this kind.

However, when I began to think about the biological clock theory in detail, I began to have serious doubts about it, for two main reasons.

First, this theory did not make sense in terms of evolution. There is undoubtedly a strong evolutionary basis for biological clocks that underlie daily rhythms. Circadian rhythms help organisms adapt their activities to the natural cycles of day and night, and are found in many kinds of animals, including insects, and also in plants. But nothing in our evolutionary history would set a precedent for waking precisely at, say, 4:45 a.m., in order to catch an early flight. Mechanical clocks themselves were invented less than a thousand years ago, and until the invention of chronometers in the eighteenth century, they were not particularly accurate.

Precisely standardized clocks first became important in the determination of longitude, for navigation at sea, starting in the late eighteenth century. Only with the building of railways and the invention of the telegraph in the nineteenth century were clocks precisely synchronized on land, because of the need to operate railways according to fixed timetables. Synchronization is now continually maintained through wireless signals synchronizing electronic devices.

We take all this for granted, but it is a surprisingly new phenomenon. So is the wearing of watches or the carrying of smart phones by most people. Industrialized societies depend on precise timing and punctuality. Traditional, preindustrial societies were far less obsessed with exact timing, and had a more relaxed and approximate attitude, as anyone who lived or travelled in a predominantly rural society will know.

Thus, for the vast majority of human evolutionary history, there would have been no need for people to be able to wake in the night at unusual times with a precision of a few minutes. How could this ability have evolved so rapidly on the basis of an approximate biological clock? The very word circadian expresses the essentially approximate nature of these rhythms (in Latin circa means “approximate,” dies means “day”).

Second, I realized that my own time sense was not particularly well developed in the daytime. I could often guess the time with an accuracy of about ten minutes, but I was sometimes off by more than half an hour. For many years I did not wear a watch or carry any electronic devices, and as a result developed a better time sense than most people I know, but still my daytime performance was far poorer than my accuracy at night. Why?

I was unable to find any answers to these questions in the scientific literature, so I tried to discover more by asking friends and acquaintances. I soon found that most people had had similar experiences to my own. Even dogs can respond to alarms in advance. For example, David Klein, who lives in California, noticed:

Our German shepherd shows up beside our bed just seconds before our battery-operated clock goes off. It’s as if she doesn’t want us to be late for work. At first I thought she must hear something actually working inside the clock, but it makes no noise. It doesn’t matter what time we set it for, she’s there. I have actually tried to screw up her usual waking times and have lain in bed waiting, and sure enough she shows up.

An opportunity for a more detailed inquiry some years ago when I was a visiting scholar at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. With the help of a very bright group of graduate students, I explored in more detail how the time sense seemed to work when people were awake and asleep. In this group of forty-nine people, to my surprise every single one had experienced waking up just before an alarm went off. Some commented that they could also program themselves to wake at particular times even without an alarm clock.

Was this just a matter of routine? No. Thirty-four people (79 percent) had found that they still woke up before the alarm when it was set for a nonroutine time. Most of the others could not remember if this had happened or not.

How soon before the alarm was due to go off did they usually wake? Seventeen said within two minutes, and fourteen within five. That is to say, a total of thirty-one people (63 percent) woke in five minutes or less before the time the alarm was set for. By contrast, when it came to guessing the time during the day, most said they were often wrong by half an hour or more. This was indeed the case, as I found by suddenly asking everyone to guess the time without looking at clocks or watches. Some were wrong by as much as forty-five minutes, and most of those who were reasonably accurate said they had recently looked at their watches.

You can try this with your family or friends. Without warning, ask them to guess what the time is. Under most circumstances I expect you will find most people’s guesses are inaccurate, often out by 15 or 30 minutes. Yet the same people will probably say they have woken a few minutes before an alarm goes off at night.

I carried out further surveys by means of questionnaires at my lectures and seminars in London, in Chicago, and in Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz, California. Altogether I questioned 377 people. The pattern of results was almost the same in all these places. Overall, 96 percent said that they had woken just before an alarm went off. Only 1 percent said they had not; 3 percent were not sure. Eighty-eight percent said this had happened even at nonroutine times; 2 percent said it had not; 10 percent were not sure. Most people said that they also woke up shortly before telephone wake-up calls, just as they did before alarm clocks went off. However, a few people said that when they had to get up early, they were so worried about oversleeping that they kept waking up all through the night or couldn’t sleep at all!

In addition, most people (73 percent) said that they could program themselves to wake at a particular nonroutine time even without an alarm clock. For example, “I can tell myself what time to wake up in the morning before I go to sleep and will wake up within five minutes of that time.” Another person said: “I am self-employed and don’t wake up at the same time every day. I can program myself to wake up at any time I wish, no matter how tired I am. I am always within five minutes.” Some people were so confident of this ability that they did not need an alarm clock at all. Others were less confident and used an alarm “just in case.”

These surveys confirmed that most people have a much more accurate time sense when asleep than when awake. Why should this be so? The more I thought about it, the more surprising it seemed. During the day we receive all sorts of external clues, like hearing clocks chime, looking at watches or phones, and hearing the time on the radio, as well as natural clues like the position of the sun. This should make it easier for us to know what time it is. At night we receive very few clues for hours on end, and yet we are far more accurate. Also, we have twice the chance of guessing accurately during the day because errors could go both ways: the guess can be late, or it can be early. By contrast, at night only waking before the alarm goes off can count, because after it goes off people are awake anyway.

Could biological clocks work better during sleep, for some unknown reason? Then if the phenomenon is based on an internal clock synchronized with the daily rhythms of waking and sleeping, it should be severely disrupted when people go to bed at irregular hours, or when they are suffering from jet lag. Yet several people have explicitly told me that they can still wake before alarms go off when they are traveling and moving from one time zone to another.

Perhaps an approximate internal “clock” plays a part when people know in advance when they need to wake, but the precision with which people wake raises the surprising possibility that precognition or presentiment, may play a part as well. At first I was reluctant to take this idea seriously, but the more I thought about it, the more plausible it seemed. There is already much evidence from parapsychological experiments for presentiment – feeling the future – in the form of unconscious arousal before an emotionally arousing stimulus.

Laboratory experiments on presentiment

In the mid-1990s, Dean Radin and his colleagues at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas devised an experiment to test for presentiment in which a subject’s emotional arousal could be monitored automatically by measuring changes in skin resistance with electrodes attached to the fingers, as in a lie-detector test. As people’s emotional states change, so does the activity of the sweat glands, resulting in changes in electrodermal activity registered in a computerized recording device.

In the laboratory it is relatively easy to produce measurable emotional changes in subjects by exposing them to noxious smells, mild electric shocks, emotive words, or provocative photographs. Radin’s experiments used photographs. Most were pictures of emotionally calm subjects like landscapes, but some were shocking, like pictures of corpses that had been cut open for autopsies, and others were pornographic. A large pool of these “calm” and “emotional” images was stored within the computer.

In Radin’s experiments, two of the fingers on a subject’s left hand were wired up so that electrodermal activity could be monitored, and the subject sat in front of a computer screen. When she was ready to begin, she clicked on the computer’s mouse button. This caused the computer to select one of the photographs at random from the pool within the computer. The screen remained blank for five seconds, and then the randomly selected image was displayed for three seconds before the screen went blank again. After a rest period of five seconds, a message on the computer screen told the subject she could press the mouse button for the next trial whenever she felt ready.

As expected, when calm pictures appeared on the screen, the subjects’ emotions remained calm, and when emotional images were displayed, the subjects were emotionally aroused, as shown by an increase in their electrodermal activity. The interesting thing was that when emotional images were about to appear, the increase in electrodermal activity began before the picture appeared on the screen. The subjects’ emotional arousal began three to four seconds in advance. However, when they were later asked if they had been conscious of what kind of pictures were about to appear, almost all said they were not. Their presentiments were largely unconscious.

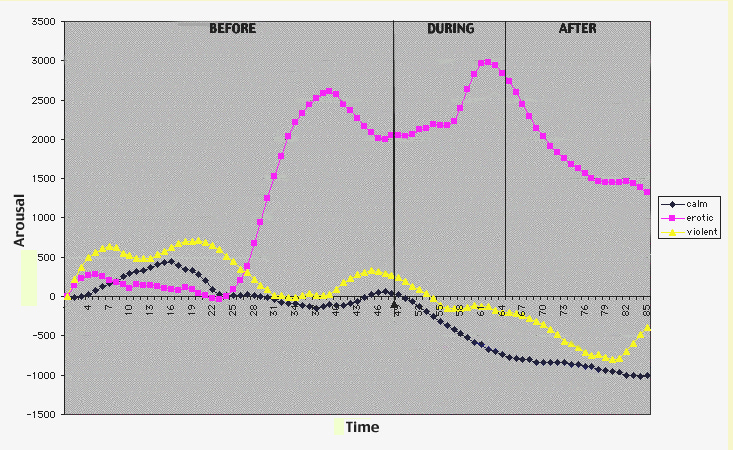

Dick Bierman, a professor of psychology at the University of Amsterdam, independently replicated Radin’s experiments in the Netherlands. As in Radin’s experiments, subjects showed significantly more emotional arousal before emotional images appeared on the screen than before calm images appeared. Bierman also found that the erotic pictures tended to be more arousing before they appeared than did the violent ones.

I myself served as a subject in one of Bierman’s tests, with the results shown above. I had a strong emotional arousal before the erotic images appeared, even though I was quite unconscious of it. The dramatic rise in my electrodermal activity began five seconds before the pornographic pictures came up on the screen. No such arousal occurred before the calm images appeared, or even before the violent ones.

I had already read about Radin’s and Bierman’s experiments when I did this test, and had been impressed by the remarkable effect they had discovered. But I was amazed to find how well the test worked when I was a subject myself, and to see such clear-cut results from an experiment that lasted only about fifteen minutes. Since the randomization was automatic and took place inside the computer, there was no way I could have detected by any “normal” means what kind of picture would come up next, nor could I have picked up any clues from Bierman. He did not know which images would appear, and in any case he was not in the room when I did the tests. I was alone with the computer, the images, and my emotions.

What about unexpected alarms?

An alarm clock gives a great shock to the system. It is indeed an alarm. The Italian root of this word expresses the idea clearly: all’arme means “To arms!” By dictionary definition, an alarm is “a call to action,” “news of approaching hostility,” or “a sound to warn of danger.” Any animal or human that could wake before danger or approaching hostility would have a better chance of surviving than one that did not. Waking before alarms makes good evolutionary sense. All animals are vulnerable when asleep. Animals that can anticipate danger and wake up in advance are likely to be favoured by natural selection.

An alarm going off in the night is literally arousing. This could well be preceded by a physiological arousal, as in the presentiment experiments. If this is the case, then more alarming alarms should have more effect than less alarming ones. A few people have spontaneously commented on this. For example: “I very often wake up one or two minutes before my alarm goes off. This happens frequently when I use a very loud, unpleasant-sounding alarm, but rarely when I use a quieter, less unpleasant alarm.” I do not know how many other people have had this kind of experience.

It should be possible on the basis of evidence to decide between the clock hypothesis and the presentiment hypothesis. What would happen if people were woken in the night by alarms that they did not know about in advance, such as fire alarms, or unexpected loud noises? On the presentiment hypothesis, waking in advance should still occur, but on the biological clock hypothesis, it should not. To find out if anyone had noticed that they woke before unexpected alarms, in my surveys I asked, “Have you ever found that you have woken up just before an unexpected alarm or event?” To my astonishment, a majority, 53 percent, answered yes; 16 percent said no, and 31 percent were not sure.

Not all awakenings before alarm clocks are followed by alarms or loud sounds or other causes of arousal. As discussed above, many people wake up before the time for which the alarm is set, and then turn the alarm off before it sounds. And many wake at a predetermined time without using an alarm clock at all. In both these situations, waking cannot be a result of a presentiment of the alarm actually going off. So, of what could it be a presentiment? It must be of the time the clock is showing when we look at it after we wake. Even people who can wake without an alarm must look at a clock or watch after they have done so, otherwise they would not know that they had woken at the right time.

But what if people are woken by unexpected disturbances? If there is an explosion nearby in the night, for example, or if a fire alarm goes off, do some people still wake shortly beforehand? Apparently, some do. For example, a fireman in Australia told me about his experience when he was sleeping in the fire station as part of a crew that was on duty, to respond to call that came in “Whenever the alarm would go off in the night I would regularly wake up 5 to 10 seconds before the siren would sound. It was uncanny. I would regularly sit up and put my feet on the floor just as the alarm would start to sound.”

For most people being woken by an unscheduled alarm or siren is an unusual experience. But for firefighters and others in emergency services, it must be more common.

Waking shortly before unscheduled alarms of disturbances clearly cannot be explained in terms of a time sense, and would favour the presentiment hypothesis.

If you have experienced waking soon before unscheduled alarms or sirens, I would be happy to hear about your experiences as part of my ongoing research. Please email me at sheldrake@sheldrake.org

I have had a regular game with myself for years - When I wake up whether in the morning or intermittently at night, I guess the time before I look at the clock. I typically wake up briefly 1-2 times at night so I'll do this experiment several times a week. I have not recorded the results, but anecdotally I would say I guess the time fairly closely 75% of the time, many times very closely. Just a couple nights ago, I woke up and said to myself it is 3am and the clock said 2:59am.

This recalls a drug induced experience from my teenaged years where high on cannabis, I had been sitting with friends in my bedroom for a few hours hanging out and talking. I was quite late and we were tired and I unconsciously blurted out, it's 2:39am! and whirled around to look at the clock and it was that time exactly.

My subjective experience of waking at night is that the time first has a feeling to it, like it distinctly feels to be a certain time.

When my children were very young, I always woke at night with a sense of anticipation that they would soon wake too, and need mother. Even if there was no obvious indication when I first awakened. I would look over at my husband, and he would be fully asleep at such times.